By Loraine Hutchins

Editor’s Note: Last year, Loraine Hutchins turned 70. Her health is declining. She is having a hard time walking without her walker or cane, and she doesn’t want to be alone. She has no kids or partner, so she opted to move to Friends House, a CCRC (continuing care retirement community, which includes independent living residences, assisted living, and a nursing home) on the edge of Washington, DC in Sandy Spring, Maryland. Friends House was founded by progressive Quakers fifty years ago as a low-income housing alternative. There are also market-rate cottages and lodges and the administration has engaged in a training project with SAGE (Seniors Advocating for a Gay Environment) to make Friends House an LGBTQ-inclusive facility. Sandy Spring has long been a Quaker enclave. It was one of Harriet Tubman’s underground railroad stops and there is a local black community there with descendants from some of the first freed black people before/after the civil war. This essay is Loraine’s reflection on her experience living there.

How do we hold council on a foundation of mutual respect?

Last weekend, one of my neighbors voiced worry about whether someone on the hall can cope with her current medical emergency. The staff person who would try to handle that situation left her job, and we don’t yet have a full-time replacement. Aware of lack of staff, residents often keep their mouths shut and don’t ask for help or voice their needs. A helpless/hopeless attitude contributes to isolation, depression, physical/mental decline, something this community and Aging Well With Friends1 was intentionally designed not to do.

I’ve asked elders to explain the values that are important here, the history. I’ve also asked, “What are the models for conflict resolution?” and “How do we get our needs met for more community change when we don’t see an available vehicle?” Most people tell me to find others and to form a committee to work on a project or make change.

Others respond in bafflement or silence with at least a side order of dementia.

The silence, and the side order, speak loudly about how we, this community, deal with conflict. Conflict is not easily addressed; is often suppressed, managed, manipulated. Residents are humored, reassured that “things will get better soon, after construction,” and asked to volunteer more2 to help activities go on during all the transition and chaos. I am grateful that people respond and connect.

What I most want to talk about is what interferes with deeper community building and ties between people, stretching toward that “foundation based on mutual respect.” What gets in the way?

In interactions I notice my mind constantly assessing which people are totally here, which ones are on cruise-control, with their own personalized touch of dementia, dizzy spells, memory lapses, not-finding-the-words that come and go. Some people I thought were fully here, aren’t anymore. Some I thought were really disoriented share moments of lucidity and insight that I didn’t expect.

What does all this mean to an intentional community designed to do decision-making and community-maintenance together, when one is never quite sure whom one can count on or how much of oneself is remembered or known?

The deep silence I hear, living-close-together is something very private and almost shameful, we refrain from talking about: personal decision-making around our health, finances, and end- of-life planning (or lack thereof)—all that stress. Even when we share bits and pieces, we keep the scary parts to ourselves.

Someone is afraid people will realize she needs more assistance, will kidnap her and tell her what to do.

Someone books a trip to France to study ancient cave art; another registers for a summer writing retreat in the mountains.

Someone is afraid of retiring and facing her chronic health challenges.

Someone can only afford to eat one meal a day, and worries about paying for his funeral; another doles out their insulin so they can pay bills for the month.

Someone wants to die, can’t ask for help, drinks all day to dull the pain instead.

Someone lives in a creek-side cottage, delighting in gardening, human contact, artistic expression.

Someone is hearing too much of the construction noise. The dust surrounds them; they keep falling down in the mud.

Someone worries her mom in assisted living is neglected, doesn’t know how to use the staff and resources to advocate for her mom.

Someone was just diagnosed with dementia and is scared to talk about it.

Someone just fell in the bathroom and can’t get up.

Someone sits in the sun by the pond writing a poem for their own funeral.

Someone serves her dinner guest homemade pear chutney her deceased husband made back when he was alive, seven years ago; the piquant end of it trickles out of the jar, savored like a sacrament.

Some of the hidden underground springs are rising. Some of the ghosts haunting the hallway may be ancestors leaving cautionary messages.

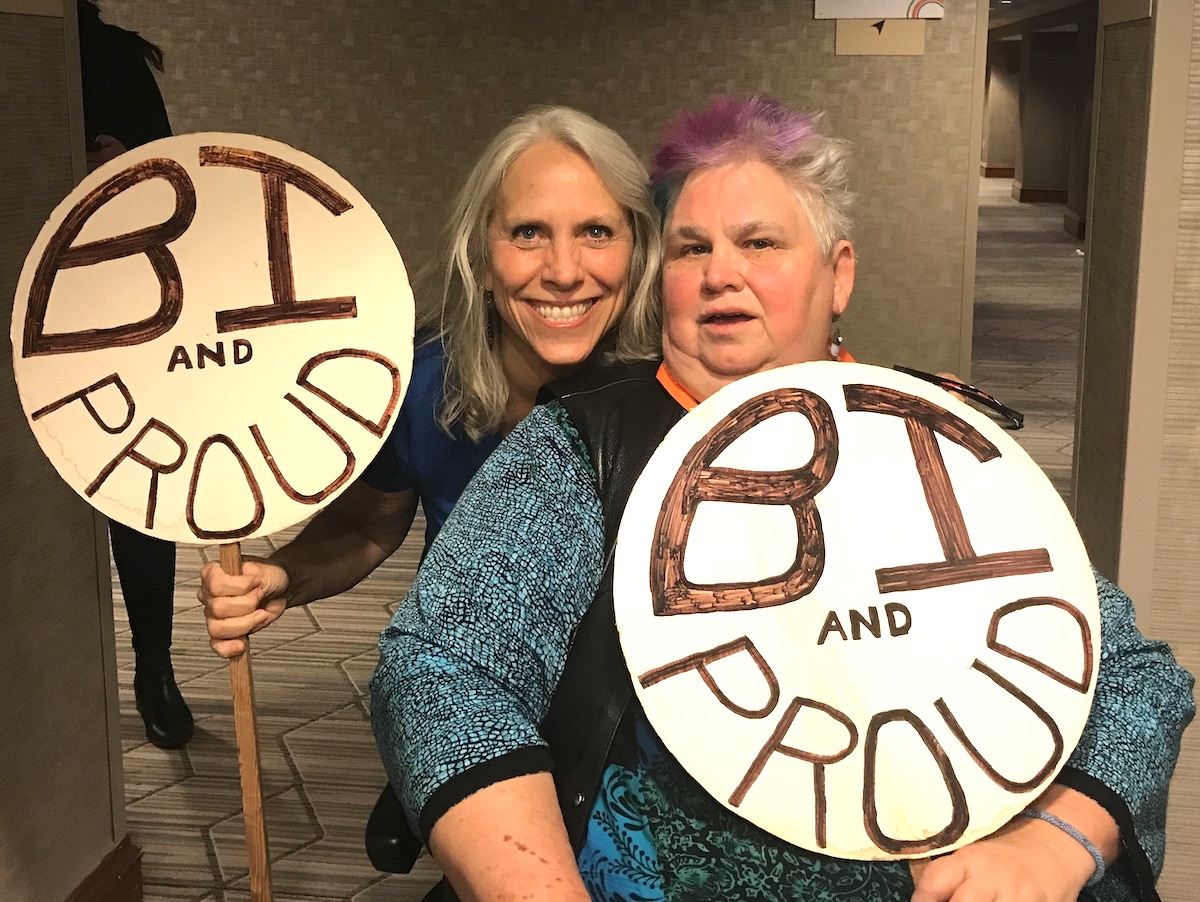

Loraine Hutchins co-edited Bi Any Other Name: Bisexual People Speak Out. She co-founded BiNet USA, served on its first board of directors and helped organize AMBi, the Alliance of Multicultural Bisexuals, in Washington, DC. Her graduate studies focused on queer feminist sacred sexualities. She serves as book review editor for the Journal of Bisexuality and taught interdisciplinary sexuality courses at her local community college for a dozen years.

1 A grant program at Friends House, supported by Friends Services on Aging.

2 Residents protested cessation of Free Food Program. Staff response: Let the residents run it themselves.