By Rosemary Van Deuren

My great-grandmother was an Irish Catholic woman who married a Jewish man – my great-grandfather – something that was not always done a hundred years ago, even though it was called the Progressive Era. Kit O’Brien died as a young woman in a Chicago hospital of what was recorded as “bowel obstruction.” She left behind three children, aged five, six, and seven, and one man, suddenly a single parent. Bernard Winsberg, a traveling salesman who either did not feel fit to care for his children, or did not want to, eventually opted to send the children to Catholic boarding schools for girls and boys. Bernard had not been practicing Judaism since before his first marriage, but it was never clear whether he chose Catholic institutions at the urging of his new wife, out of convenience, or out of loyalty to the children’s mother.

When I was five years old, I saw Harry Lachman’s spectacular 1935 Dante’s Inferno on cable television at my Grandpa’s house. I was young enough to liken all people to myself, and assumed everyone in this hellbent world to be of integrity, and innocent. When I saw their bodies crawling up a rockwall edifice and tumbling into pits of fire, I imagined they were just adult versions of me, writhing before my eyes, ready to suffer the torments of disembowelment and more. I told my mother I was afraid I was going to hell.

At eight years old I sat bent over on the hard pew in church, with my head between my knees. I always struggled with the Via Crucis – the Stations of the Cross – because the mass was too long and the incense was far too strong. Year after year that gray circle that began around the edges of my vision crept in as I began to feel woozy. My teacher didn’t want me to drop over in the middle of the Stations, so she told me it was ok to sit and recuperate. The worry that I would pass out was replaced by the concern that God would be mad at me because I couldn’t stay on my feet until Jesus was laid in the tomb.

By the time I became a teenager, I could hardly keep from falling asleep during weekly mass at all, at times staying awake only through the fabrication of very un-church-like thoughts. The sermons were increasingly inconsistent with the person I was becoming, and I wasn’t getting enough sleep at night. I was always anxious for communion because I never got up early enough to eat breakfast anymore, and I was so, so hungry. Hungry for food. Hungry for solace. Hungry for attention. I was sprouting up quickly and I had breasts, both because I wanted them and because fate is cruel, and I was often mistaken for older than I was. I didn’t wonder whether God was angry at me anymore, because I didn’t care. I knew I wasn’t going to hell, because I knew, then, that not everyone was like me, for there were people in this hell-bent world far more sinful than I was.

I didn’t even believe in hell anymore.

When I was seventeen, I was back in Catholic school again for a semester – private school, in Milwaukee. My religion class went on a field trip to the local synagogue, where my classmates were skeptical that the kindly and white-haired rabbi really didn’t believe Jesus was the son of God. They were prepared with the rhetoric that was their truth, and made arguments which were beyond preposterous for this scenario. I was stunned by how disrespectful it seemed to me – as we were guests in a place of worship – and also, so incredibly naive. Did these teenagers, children in the eyes of an educated Talmudist, actually believe they could convert a sixty-five-year-old rabbi to Catholicism? As though they could make any argument he had not already considered or been confronted with. I couldn’t understand why they were so antagonistic at the prospect of someone finding consolation and resonance with something other than what they found familiar. I did not ascribe to either faith and never would again, but was nothing if not respectful.

That same year, I returned to public school. My weekends were spent as they had been before, in night spots and beater cars, and out in the country where no one held you accountable for whatever kind of entertainment you could wrestle up. When I came home at night, dirty and reeking of myriad kinds of smoke as I bumped into chairs in the dark, I thought I had balls as true as a man’s – fearless – until I had to dodge one indistinct but pervasive menace: the Fritz Eichenberg woodcut print. The Follies of the Monks from Eichenberg’s “In Praise of Folly” portfolio hung in the slate-floor room that connected the piano room and the kitchen, which I had to pass to reach the staircase, and my bed. In daylight hours I had looked at the piece many times, and it was compelling in its grotesqueness – starving peasants putting coins in the mug of a well-fed monk, a rumpled and faceless woman squeezed onto a friar’s lap, and a suspect-looking confessional, where the monk inside is ready to accost the woman relaying her sins. Bosch-esque animalized figures oversee it all, along with Henry VIII, and Jesus’ crucifixion is illuminated at the top, contextualizing the satire in all its debaucherous glory. The piece wasn’t my mother’s; she preferred Chagall – The Green Violinist and Over Vitebsk, with soft-edged, dreamlike palettes and saltof-the-earth imagery. The Eichenberg print was disturbing, and I liked that – during the day. At night, I refused to look at it; I could not. But even while averting my eyes I already knew intimately the appearance of the twisted faces and robes that had been carved into the wood block from which it was printed. And the Christ figure’s gaunt misery at seeing the antithesis of what he presumably hoped his martyrdom would achieve. It was not the religious aspect of the artwork that frightened me, but the flip-side of religion that it represented. If everything in the world that was meant to enhance existence was, in reality, just futility spiraling out into despair, that meant effort was worse than meaningless: it was an insult, a trick – an Ouroboros feasting on the naivete of the population, feeding itself for all eternity. The interpretation presents Jesus as less of a Christ figure and more of a man, forced to acknowledge in his dying moments that all he’d worked for in life was a farce. Coming home from a night of clubbing under strobe lights, I would run past Eichenberg’s depiction of the crucifixion without looking at it, like Perseus fleeing Medusa or a frightened child rushing away from a dark bedroom closet.

You think that if you can memorize the clutch of someone against you, you’ll be in some way connected to whatever static permanence life might have had, even when it’s over. It can help you pretend you’re outside of the realm of mortal culpability, as if time has stopped. Youth requires less cajoling to make things feel permanent. As we grow older, that perception of what is lasting grows more indistinct. You become obsessively homed-in to the things that make you feel linked to a sense of longer time and higher meaning: Walking outdoors. Seeing a deer wading through a river up to its stomach. Eating food that’s meant to be consumed unaltered, in its original form, like an apple. Giving pleasure. In exerting complete control over someone else’s body, you fill their awareness with nothing but what you have to offer their physicality, their euphoria. That is the kind of immortality that can only be achieved by functioning in service to another person to the point that, in that moment, they can’t imagine anything outside their world but what you are capable of doing to them.

Everything in life becomes a distraction to fill the years before your imminent departure; a pursuit to best realize your existence before you submit to the unknowable void. If by some incredible feat you do meet every one of your mortal goals and make all the progress you can, will you still be satisfied with the time contained within your lifetime? In the end, will you attribute meaning to what you’ve accomplished by how you feel about yourself, or by how you are viewed by those around you? You wonder if you’ll be able to charm your way into a better-quality afterlife using the manipulation skills you’ve learned on this mortal coil. With family extending back generations, setting the tone for what is to come and creating the stage for what you’ll withstand, how much control do you actually have over how your life plays out? Is it less than you think?

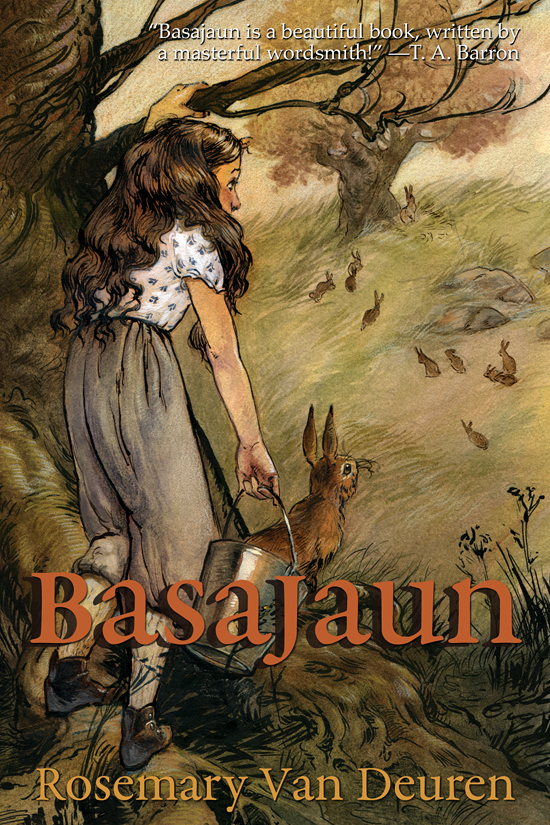

Rosemary Van Deuren is a novelist, essayist, and arts interviewer. She is author of the adventure fantasy novel Basajaun.